Introduction

Awajún or Aguaruna is an ethnic group living in the San Martín, Amazonas, Cajamarca and Loreto regions of Peru. Its territory reaches up to Ecuador where the Awajún people are known as Shuar. From the linguistic point, they belong to jibaro family which includes also the Huambisas, a native tribe of Peru, living on the upper Marañón and Santiago rivers.

The result of the National Census 2007, which is currently the ultimate reference of population in Peru, indicates that Amazonian indigenous population reaches 332,975 people. The Awajún make up the second largest ethnic group in the Peruvian Amazon with a population of 55,366 inhabitants (over 50% of the population is underage).

According to M. Brown (1984), the first note about the Jibaro is connected to Incas Túpac Yupanqui and Huayna Cápac’s intention to extend their dominion across the region of Jibaro society, including the Awajún. Spanish conquistadores first contacted the Jibaro in 1549 when they were founding the Jaén de Bracamoros City, and then Santa María de Nieva (nowadays the capital of Condorcanqui province in the Amazonas Department). Without a doubt, the objective of these colonists was the exploitation of gold deposits in the region, followed by enslaving the indigenous population. As a result, the Jibaro people rose in rebellion in 1599 and largely drove the Spanish out of the region.

There were many unsuccessful attempts to conquest the Jibaro till 1600. Finally, it was prohibited to continue Jesuit missionary work among the population in 1704. At the beginning of 20th century, the relationship between the Jibaro tribe, white colonists and mestizos was still hostile. Nevertheless, in 1925 the protestant mission was established among the Awajún, and in 1947 a group of linguists was sent into their territory. In 1949, the Jesuit order established its mission in Chiriaco, so from the half of 20th century, the Awajún population got a school education.

At the end of the last decade, the creation of regional organizations strengthened the ethnic identity of Awajún, consolidated their territory and established community development programmes.

Awajún Spirituality

The spiritual world of the Awajún is led by five Gods:

- Etsa, or the Father Sun, destructor of Ajaim, a demon who came into existence at the beginning of the world.

- Nugkui, or the Mother Earth, who provides fertile ground and soil for the ceramics.

- Tsugki, or the Mother of Water (or Rivers), who lives in the rivers.

- Ajútap, or the Father Warrior, the spirit of ancient warriors who continuously reincarnates.

- Bikut, or the Grand Philosopher Awajún, a legendary being which transforms into toé (Brugmansia suaveolens), a psychoactive plant which mixed with ayahuasca (Banisteriopsis caapi) produces altered states of consciousness. Its consumption is essential for the Awajún spirituality, because it helps the indigenous people to connect with other superior worlds.

According to Awajún people, each man has two souls: , which reaches the sky, and , seated in the Earth as a little demon. They also believe that the jungle is full of souls of people who transformed into trees and animals. Animism, i.e. system of beliefs where the nature is considered as intelligent, is also typical for the present day mestizo spirituality, although here it is combined with the principles of Roman-Catholic religious ideology.

The Awajún cosmovision, majorly inspired by the ritual use of psychoactive plants or so called plant teachers, as they are referred to in the indigenous terminology, has been transmitted orally from generation to generation. (Luna, 1984) The principal medicinal plants of Awajún ethnobotany are tsaag (tobacco), el datem (ayahuasca) and tsuwak (toé). Además, en su mundo espiritual, el awajún cree en cinco dioses:

Psychosocial conflicts

The contact with the Western world was fatal for Awajún society, because it caused the invasion of colonists and multinational companies exploiting petroleum in their territory, as well as the deforestation and contamination of forests and rivers. Thus many indigenous political leaders and organizations (NGOs and churches) have emerged to represent the Awajún and protect them against the state, although not always successfully.

The absence of a Peruvian development policy for indigenous groups brought about as consequence many problems of the Western world. Extreme poverty (≤ 32,6 % in 2009), migration, malnutrition (22,2 % among children younger 5 years of age in 2009), maternal (3 % in 2005) and infant mortality (17,1 per 1.000 in 2008), followed by psychosocial problems, such as gangs, thefts, drug trafficking, absence of cultural identity, depression, suicides of adolescents, absence of the meaning of life, alcoholism and drug addiction (mostly to marihuana, inhalants, cocaine or basic cocaine paste) are the consequence of a missing transparent policy supporting indigenous communities and respecting their customs and traditions.

An ancient culture able to defend itself firmly against the invasion of Incas is nowadays weakened in its cultural identity and threatened by the government to lose its lands. It is also obliged to Evangelic church in leaving its medicinal and religious practices in an atmosphere of manipulation and fear, in extreme cases promising before God not to continue in the use of its medicine and practice its traditions because they are considered as witchcraft. In the course of time, the Awajún culture has resulted in the state of vulnerability and defenselessness, principally in the juvenile population.

Necessity to take up tradition – Purgahuasca

For millennia, traditional cultures showed that they have always been able to deal with difficulties through maintenance and practice of their traditions. The so called psychosocial problems known in Western culture did not exist here and if they occurred, there were resources available to address them. These vicissitudes were taken by elders’ (apus) advice, who together with the community designed an intervention plan.

When young people reached a certain age of puberty or adolescence, there were initiation rites to be passed, i.e. ceremonies conducted by father or mother depending on the sex of the adolescent. In other cases, they were also led by apu (a wise leader). In these ceremonies certain psychoactive plants (ayahuasca and/or tobacco) were ingested, so the initiated could contact the spirit world and get from this dimension answers to their concerns in personal and community life. These ceremonies demanded both physical and spiritual preparation because they could last from one night to several days. At the end of the ritual, the young man became an adult; he was assigned the woman who would become his wife (also initiated by women), he obtained his land, where he built his house, seeded crops and breeded animals for food.

This type of procedure could also cure physical and spiritual illness. However, it is observed that these rites are almost no longer performed. Interventions of religious groups brought Awajún not only access to education, but also caused the loss of some of their customs, in this case their medical practice. Many healers were forced to give up their medical practice in order to gain access to christening and not to be labelled as practicing witchcraft and being called "witches" because their practices were associated with witchcraft and death. So, healers were gradually leaving their practices and the most noticeable result is that currently no youth want to learn them, because they have a very negative connotation.

Chacrunita pinturera... Tabaquero y curandero... Agua floridita y cuna... Ushpawasha sananguito... Bubinsana hay curandera... Yaku sisa curandera... Ajo sacha hay curandero....

Experience of Takiwasi Centre

Takiwasi, Center for the Rehabilitation of Drug Addicts and for Research on Traditional Medicines, which has since 1992 applied in its therapeutic programme the ritualized and controlled use of medicinal plants with psychoactive effects since 1992, has been requested for its therapeutic approach by the people from Awajún communities, who presented various psychosocial problems. The Treatment included ritualized administration of some plants and rites used by their ancestors. Experience with some youth and adults has been quite positive in healing and personal evolution, to the point that these people have become agents in revaluation of traditional medical practices in their communities.

The ceremony called Datem umaja imutai waimaktasa (i.e. “the vision of future”) or purgahuasca in Spanish is one of the therapeutic methods of the Awajún culture and since November 1998, it has been included as a practice within the therapeutic protocol of the centre. Nowadays its application has become more popular compared to recent years, with the frequency from two to three months. The amount of the substance that the patients use under the control of the healer and his two assistants has also changed significantly. Unlike in the past, nowadays what makes the rite typical is drinking at least three litre bowls of the substance instead of five.

The purgahuasca is a ritually prepared decoction of datem, with some leaves of yagé (Diplopterys cabrerana). It's a strongly diluted potion with powerful emetic effect. There is also visionary and teaching effect present. Using purgahuasca induces an unmoving trance characterized by a severe inebriety (mareación), physical tremble, perspiration, discomfort and vomiting.

Healing songs or icaros in local terminology, piped or sung in indigenous languages, followed by a rhythmical crackling made by shacapa (a rattle from palm leaves or healing plants), are used to harmonize such a state and poise it.

The process of purgahuasca preparation takes one day. The whole procedure lasts approximately twelve hours, starting before 6 a.m. and finishing at 5 p.m. Boiling of purgahuasca is one of the healer assistant’s responsibilities. He transports a sixty-litre pot with the extract to the big maloca, an oval building where the ceremony traditionally takes place, at early-evening hours and lets it cool down at an acceptable temperature. The ceremony begins as soon as the temperature is right.

Description of Purgahuasca Ceremony

The following chapter contains a description of the purgahuasca ceremony we participated in during the field work in the Takiwasi Centre in 2009. Regularly it starts after the mass at 6 p.m. Then, twelve participants take their seats on wooden chairs in the circle in a big maloca and at first they listen to a lecture about the tradition of the purgahuasca use. The healer motivates them not to lose their confidence regarding the constant close control over them. The patients are encouraged to make every endeavor to drink up the prescribed amount of the substance.

The circle is full of tension. Some patients are confident enough to handle the whole situation by themselves and drink some extra bowl for their health, on the other hand, others show fierce resistance and are unsure whether to stay or not because it is not allowed to leave the session once it has started.

Then, everybody in the circle is sprinkled with holy water and censed with tobacco. Subsequently, the cooled beverage is cleansed by mapacho smoke, taken in the healer’s mouth and blown out to all the four cardinal directions.

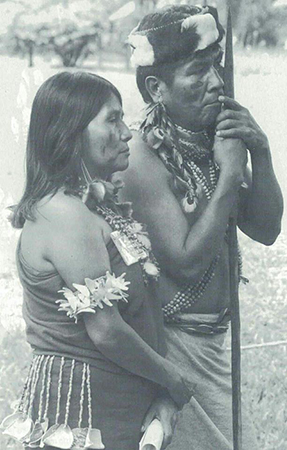

Afterwards the patients are asked to turn up their right trouser-leg, take off their shoes, and one after another step forward to the healer, who leans on a high stick and there is a boulder in front of him. Everyone stands on it; the healer sets foot on their foot and censes it with purgahuasca.

Then they all take their bowls of warm extract and start drinking. The healer starts singing an opening icaro Paparuy and his assistants walk around the patients. During an individual treatment, they listen to the song Ayahuasca Curandera Shamoaycuna Cayari and the spirits of all the plants from the adjacent botanical garden are euphemistically invoked.

The healer walks around the patients and stops at each of them. He fans their bodies and sings. In accordance with his intuition, he calls from an immense range of the spirits of plants the one that would be able to become an adequate ally for them at the particular moment and help them to cope up with their personal obstacles.

Approximately in two hours, the patients start to go to sleep one by one. Nevertheless, not everyone manages to fall asleep. During the night many of them get up to fill up their buckets or grope their way to the toilet. In the end, everything quiets down. Sporadically, flashing lights of assistant’s lantern fly through maloca, unwittingly letting everybody know his presence and by that securing the participants’ sense of safety.

He turns the lights on at five o’clock in the morning and calls upon them to wash in the river. The session ends at a collective breakfast when there is served an onion salad with salt, a pinch of yellow chilli and lime (the so called corte de dieta) and then chicken broth. A substantial soup with rice and boiled bananas strengthens those who slept badly at night because the programme of the following day is the same.

Analysis of Purgahuasca Experience

In Takiwasi patients treated for drug addiction participate in purgahuasca session every two months, i.e. during nine months long treatment they pass through five or six sessions approximately.

After the session, each patient must fill out a survey with questions about the physical and psychological effects of purgahuasca, which also includes a drawing describing the personal experience.

All the material produced by purgahuasca during the session is discussed and integrated in Takiwasi through a group dynamic, led by a therapist who, from the psychological analysis of patient’s thoughts, insights, visions or dreams, comes to a conclusion shared with him during an interview. The patient talks about his experience to other people in the group, who in turn can make contributions, thus giving rise to an exchange of feelings and opinions That are intended to serve as instructions in daily lives, within the community and during treatment.

The exchange of personal experience of drinking purgahuasca and other plants, directed by a therapist, is essential in the Takiwasi treatment because it permits to convert its symbolic content to the concrete, and behavioural. This process is seen as principal in the rehabilitation and personal evolution of patients.

In order to find out what kind of phenomena occurs in the content of patients’ purgahuasca experience, we decided to analyse the protocols of purgahuasca sessions from the years 2007 and 2009 (N=29). It turned out that purgahuasca, in the patients’ opinion, induces visions approximately in a quarter of cases, their content is from more than a half made up of the visualizations with semantic content (e.g. mandalas, tunnels and difficult labyrinths) that are to a great extent modulated by a musical accompaniment. In addition, they include paintings of various objects and situations from personal life beyond which emotional and significant connotations can be found (the picture of a knife, three quartered persons, accident, etc.).

Conclusions

The results of our nine months long field work realized in the Takiwasi Centre in the years 2007-2009 showed that 27 % of internal patients, who were treated here from 1999 to 2009, reached such state that they were considered cured by therapists. Nevertheless, based on the participant observation, it is evident that such data does not tell much about the effectiveness of the rehabilitation programme. In fact, some patients got rid of the drug addiction in less than compulsory nine months. Taking them into consideration, the indicator of effectiveness rises up to 70 %.

The content analysis of 32 semi-structured interviews with the staff and patients verified that the Takiwasi therapeutic model is based on the coherent system with a very diverse tradition of indigenous medicine, so the complex local rehabilitation programme represents an equivalent competitor to other therapeutic approaches based on total abstinence and substitution. The purgahuasca rite of the Awajún seems an important component of this system, because on one side it significantly contributes to the treatment of drug addiction; on the other side it keeps alive the tradition of Awajún indigenous medicine which is still more and more endangered by the impact of Western culture.

Published in the “Journal of Research on Contemporary Society”, 2014. v. 1, no. 1, p. 21-27.

The ritual ceremony of purgahuasca

Purgahuasca is a little concentrated ayahuasca preparation that is taken as in a purge session. This preparation mainly has a vomitive effect, with secondary visionary or teaching effects.